Warning: The below content is not appropriate for children. Please check with an adult before you read this page. To go back to the children’s page, please click here.

This isn’t an easy piece to write, for reasons that will shortly become clear, but I know it’s time to explain myself on an issue surrounded by toxicity. I write this without any desire to add to that toxicity.

For people who don’t know: last December I tweeted my support for Maya Forstater, a tax specialist who’d lost her job for what were deemed ‘transphobic’ tweets. She took her case to an employment tribunal, asking the judge to rule on whether a philosophical belief that sex is determined by biology is protected in law. Judge Tayler ruled that it wasn’t.

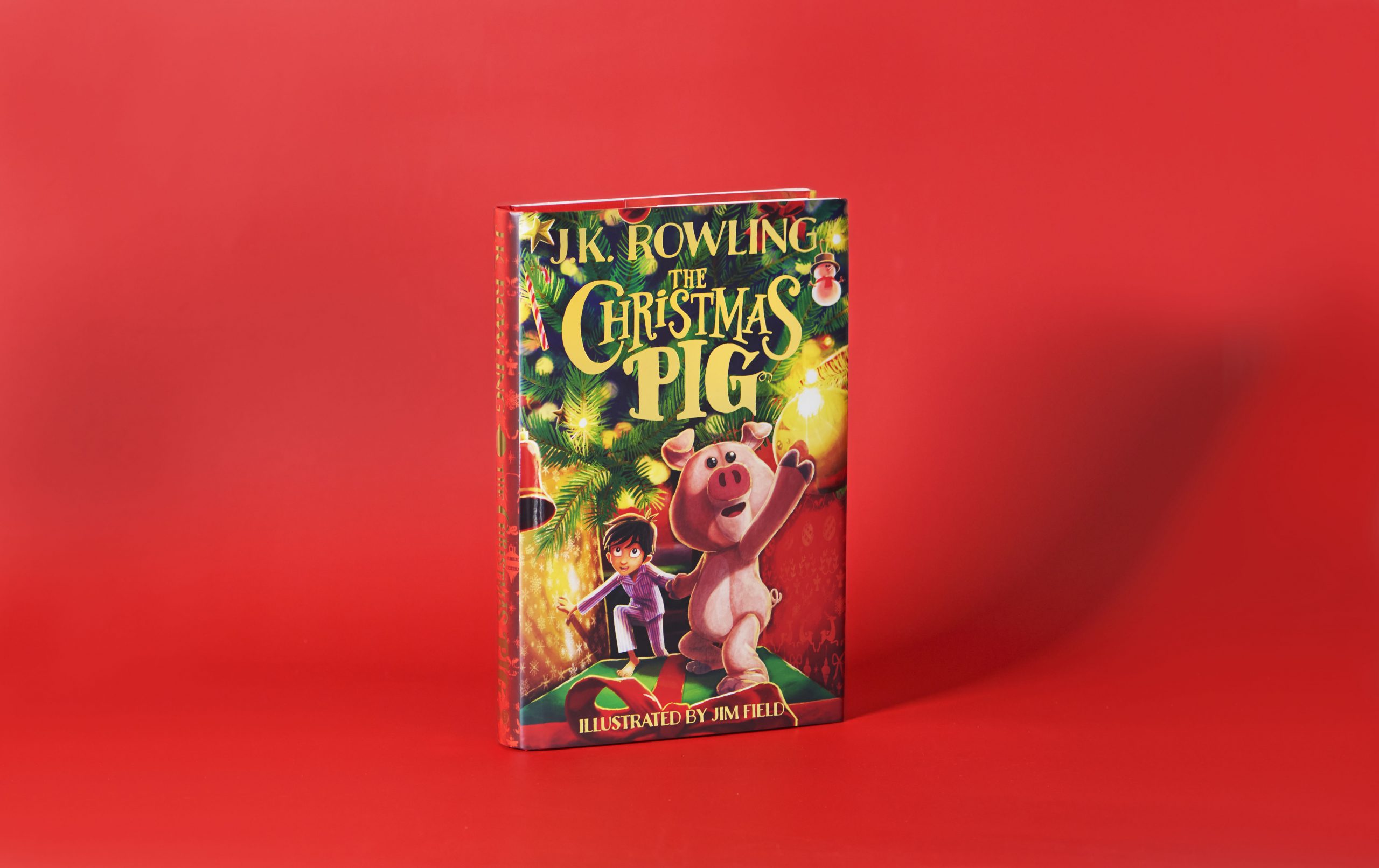

My interest in trans issues pre-dated Maya’s case by almost two years, during which I followed the debate around the concept of gender identity closely. I’ve met trans people, and read sundry books, blogs and articles by trans people, gender specialists, intersex people, psychologists, safeguarding experts, social workers and doctors, and followed the discourse online and in traditional media. On one level, my interest in this issue has been professional, because I’m writing a crime series, set in the present day, and my fictional female detective is of an age to be interested in, and affected by, these issues herself, but on another, it’s intensely personal, as I’m about to explain.

All the time I’ve been researching and learning, accusations and threats from trans activists have been bubbling in my Twitter timeline. This was initially triggered by a ‘like’. When I started taking an interest in gender identity and transgender matters, I began screenshotting comments that interested me, as a way of reminding myself what I might want to research later. On one occasion, I absent-mindedly ‘liked’ instead of screenshotting. That single ‘like’ was deemed evidence of wrongthink, and a persistent low level of harassment began.

Months later, I compounded my accidental ‘like’ crime by following Magdalen Berns on Twitter. Magdalen was an immensely brave young feminist and lesbian who was dying of an aggressive brain tumour. I followed her because I wanted to contact her directly, which I succeeded in doing. However, as Magdalen was a great believer in the importance of biological sex, and didn’t believe lesbians should be called bigots for not dating trans women with penises, dots were joined in the heads of twitter trans activists, and the level of social media abuse increased.

I mention all this only to explain that I knew perfectly well what was going to happen when I supported Maya. I must have been on my fourth or fifth cancellation by then. I expected the threats of violence, to be told I was literally killing trans people with my hate, to be called cunt and bitch and, of course, for my books to be burned, although one particularly abusive man told me he’d composted them.

What I didn’t expect in the aftermath of my cancellation was the avalanche of emails and letters that came showering down upon me, the overwhelming majority of which were positive, grateful and supportive. They came from a cross-section of kind, empathetic and intelligent people, some of them working in fields dealing with gender dysphoria and trans people, who’re all deeply concerned about the way a socio-political concept is influencing politics, medical practice and safeguarding. They’re worried about the dangers to young people, gay people and about the erosion of women’s and girl’s rights. Above all, they’re worried about a climate of fear that serves nobody – least of all trans youth – well.

I’d stepped back from Twitter for many months both before and after tweeting support for Maya, because I knew it was doing nothing good for my mental health. I only returned because I wanted to share a free children’s book during the pandemic. Immediately, activists who clearly believe themselves to be good, kind and progressive people swarmed back into my timeline, assuming a right to police my speech, accuse me of hatred, call me misogynistic slurs and, above all – as every woman involved in this debate will know – TERF.

If you didn’t already know – and why should you? – ‘TERF’ is an acronym coined by trans activists, which stands for Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist. In practice, a huge and diverse cross-section of women are currently being called TERFs and the vast majority have never been radical feminists. Examples of so-called TERFs range from the mother of a gay child who was afraid their child wanted to transition to escape homophobic bullying, to a hitherto totally unfeminist older lady who’s vowed never to visit Marks & Spencer again because they’re allowing any man who says they identify as a woman into the women’s changing rooms. Ironically, radical feminists aren’t even trans-exclusionary – they include trans men in their feminism, because they were born women.

But accusations of TERFery have been sufficient to intimidate many people, institutions and organisations I once admired, who’re cowering before the tactics of the playground. ‘They’ll call us transphobic!’ ‘They’ll say I hate trans people!’ What next, they’ll say you’ve got fleas? Speaking as a biological woman, a lot of people in positions of power really need to grow a pair (which is doubtless literally possible, according to the kind of people who argue that clownfish prove humans aren’t a dimorphic species).

So why am I doing this? Why speak up? Why not quietly do my research and keep my head down?

Well, I’ve got five reasons for being worried about the new trans activism, and deciding I need to speak up.

Firstly, I have a charitable trust that focuses on alleviating social deprivation in Scotland, with a particular emphasis on women and children. Among other things, my trust supports projects for female prisoners and for survivors of domestic and sexual abuse. I also fund medical research into MS, a disease that behaves very differently in men and women. It’s been clear to me for a while that the new trans activism is having (or is likely to have, if all its demands are met) a significant impact on many of the causes I support, because it’s pushing to erode the legal definition of sex and replace it with gender.

The second reason is that I’m an ex-teacher and the founder of a children’s charity, which gives me an interest in both education and safeguarding. Like many others, I have deep concerns about the effect the trans rights movement is having on both.

The third is that, as a much-banned author, I’m interested in freedom of speech and have publicly defended it, even unto Donald Trump.

The fourth is where things start to get truly personal. I’m concerned about the huge explosion in young women wishing to transition and also about the increasing numbers who seem to be detransitioning (returning to their original sex), because they regret taking steps that have, in some cases, altered their bodies irrevocably, and taken away their fertility. Some say they decided to transition after realising they were same-sex attracted, and that transitioning was partly driven by homophobia, either in society or in their families.

Most people probably aren’t aware – I certainly wasn’t, until I started researching this issue properly – that ten years ago, the majority of people wanting to transition to the opposite sex were male. That ratio has now reversed. The UK has experienced a 4400% increase in girls being referred for transitioning treatment. Autistic girls are hugely overrepresented in their numbers.

The same phenomenon has been seen in the US. In 2018, American physician and researcher Lisa Littman set out to explore it. In an interview, she said:

‘Parents online were describing a very unusual pattern of transgender-identification where multiple friends and even entire friend groups became transgender-identified at the same time. I would have been remiss had I not considered social contagion and peer influences as potential factors.’

Littman mentioned Tumblr, Reddit, Instagram and YouTube as contributing factors to Rapid Onset Gender Dysphoria, where she believes that in the realm of transgender identification ‘youth have created particularly insular echo chambers.’

Her paper caused a furore. She was accused of bias and of spreading misinformation about transgender people, subjected to a tsunami of abuse and a concerted campaign to discredit both her and her work. The journal took the paper offline and re-reviewed it before republishing it. However, her career took a similar hit to that suffered by Maya Forstater. Lisa Littman had dared challenge one of the central tenets of trans activism, which is that a person’s gender identity is innate, like sexual orientation. Nobody, the activists insisted, could ever be persuaded into being trans.

The argument of many current trans activists is that if you don’t let a gender dysphoric teenager transition, they will kill themselves. In an article explaining why he resigned from the Tavistock (an NHS gender clinic in England) psychiatrist Marcus Evans stated that claims that children will kill themselves if not permitted to transition do not ‘align substantially with any robust data or studies in this area. Nor do they align with the cases I have encountered over decades as a psychotherapist.’

The writings of young trans men reveal a group of notably sensitive and clever people. The more of their accounts of gender dysphoria I’ve read, with their insightful descriptions of anxiety, dissociation, eating disorders, self-harm and self-hatred, the more I’ve wondered whether, if I’d been born 30 years later, I too might have tried to transition. The allure of escaping womanhood would have been huge. I struggled with severe OCD as a teenager. If I’d found community and sympathy online that I couldn’t find in my immediate environment, I believe I could have been persuaded to turn myself into the son my father had openly said he’d have preferred.

When I read about the theory of gender identity, I remember how mentally sexless I felt in youth. I remember Colette’s description of herself as a ‘mental hermaphrodite’ and Simone de Beauvoir’s words: ‘It is perfectly natural for the future woman to feel indignant at the limitations posed upon her by her sex. The real question is not why she should reject them: the problem is rather to understand why she accepts them.’

As I didn’t have a realistic possibility of becoming a man back in the 1980s, it had to be books and music that got me through both my mental health issues and the sexualised scrutiny and judgement that sets so many girls to war against their bodies in their teens. Fortunately for me, I found my own sense of otherness, and my ambivalence about being a woman, reflected in the work of female writers and musicians who reassured me that, in spite of everything a sexist world tries to throw at the female-bodied, it’s fine not to feel pink, frilly and compliant inside your own head; it’s OK to feel confused, dark, both sexual and non-sexual, unsure of what or who you are.

I want to be very clear here: I know transition will be a solution for some gender dysphoric people, although I’m also aware through extensive research that studies have consistently shown that between 60-90% of gender dysphoric teens will grow out of their dysphoria. Again and again I’ve been told to ‘just meet some trans people.’ I have: in addition to a few younger people, who were all adorable, I happen to know a self-described transsexual woman who’s older than I am and wonderful. Although she’s open about her past as a gay man, I’ve always found it hard to think of her as anything other than a woman, and I believe (and certainly hope) she’s completely happy to have transitioned. Being older, though, she went through a long and rigorous process of evaluation, psychotherapy and staged transformation. The current explosion of trans activism is urging a removal of almost all the robust systems through which candidates for sex reassignment were once required to pass. A man who intends to have no surgery and take no hormones may now secure himself a Gender Recognition Certificate and be a woman in the sight of the law. Many people aren’t aware of this.

We’re living through the most misogynistic period I’ve experienced. Back in the 80s, I imagined that my future daughters, should I have any, would have it far better than I ever did, but between the backlash against feminism and a porn-saturated online culture, I believe things have got significantly worse for girls. Never have I seen women denigrated and dehumanised to the extent they are now. From the leader of the free world’s long history of sexual assault accusations and his proud boast of ‘grabbing them by the pussy’, to the incel (‘involuntarily celibate’) movement that rages against women who won’t give them sex, to the trans activists who declare that TERFs need punching and re-educating, men across the political spectrum seem to agree: women are asking for trouble. Everywhere, women are being told to shut up and sit down, or else.

I’ve read all the arguments about femaleness not residing in the sexed body, and the assertions that biological women don’t have common experiences, and I find them, too, deeply misogynistic and regressive. It’s also clear that one of the objectives of denying the importance of sex is to erode what some seem to see as the cruelly segregationist idea of women having their own biological realities or – just as threatening – unifying realities that make them a cohesive political class. The hundreds of emails I’ve received in the last few days prove this erosion concerns many others just as much. It isn’t enough for women to be trans allies. Women must accept and admit that there is no material difference between trans women and themselves.

But, as many women have said before me, ‘woman’ is not a costume. ‘Woman’ is not an idea in a man’s head. ‘Woman’ is not a pink brain, a liking for Jimmy Choos or any of the other sexist ideas now somehow touted as progressive. Moreover, the ‘inclusive’ language that calls female people ‘menstruators’ and ‘people with vulvas’ strikes many women as dehumanising and demeaning. I understand why trans activists consider this language to be appropriate and kind, but for those of us who’ve had degrading slurs spat at us by violent men, it’s not neutral, it’s hostile and alienating.

Which brings me to the fifth reason I’m deeply concerned about the consequences of the current trans activism.

I’ve been in the public eye now for over twenty years and have never talked publicly about being a domestic abuse and sexual assault survivor. This isn’t because I’m ashamed those things happened to me, but because they’re traumatic to revisit and remember. I also feel protective of my daughter from my first marriage. I didn’t want to claim sole ownership of a story that belongs to her, too. However, a short while ago, I asked her how she’d feel if I were publicly honest about that part of my life, and she encouraged me to go ahead.

I’m mentioning these things now not in an attempt to garner sympathy, but out of solidarity with the huge numbers of women who have histories like mine, who’ve been slurred as bigots for having concerns around single-sex spaces.

I managed to escape my first violent marriage with some difficulty, but I’m now married to a truly good and principled man, safe and secure in ways I never in a million years expected to be. However, the scars left by violence and sexual assault don’t disappear, no matter how loved you are, and no matter how much money you’ve made. My perennial jumpiness is a family joke – and even I know it’s funny – but I pray my daughters never have the same reasons I do for hating sudden loud noises, or finding people behind me when I haven’t heard them approaching.

If you could come inside my head and understand what I feel when I read about a trans woman dying at the hands of a violent man, you’d find solidarity and kinship. I have a visceral sense of the terror in which those trans women will have spent their last seconds on earth, because I too have known moments of blind fear when I realised that the only thing keeping me alive was the shaky self-restraint of my attacker.

I believe the majority of trans-identified people not only pose zero threat to others, but are vulnerable for all the reasons I’ve outlined. Trans people need and deserve protection. Like women, they’re most likely to be killed by sexual partners. Trans women who work in the sex industry, particularly trans women of colour, are at particular risk. Like every other domestic abuse and sexual assault survivor I know, I feel nothing but empathy and solidarity with trans women who’ve been abused by men.

So I want trans women to be safe. At the same time, I do not want to make natal girls and women less safe. When you throw open the doors of bathrooms and changing rooms to any man who believes or feels he’s a woman – and, as I’ve said, gender confirmation certificates may now be granted without any need for surgery or hormones – then you open the door to any and all men who wish to come inside. That is the simple truth.

On Saturday morning, I read that the Scottish government is proceeding with its controversial gender recognition plans, which will in effect mean that all a man needs to ‘become a woman’ is to say he’s one. To use a very contemporary word, I was ‘triggered’. Ground down by the relentless attacks from trans activists on social media, when I was only there to give children feedback about pictures they’d drawn for my book under lockdown, I spent much of Saturday in a very dark place inside my head, as memories of a serious sexual assault I suffered in my twenties recurred on a loop. That assault happened at a time and in a space where I was vulnerable, and a man capitalised on an opportunity. I couldn’t shut out those memories and I was finding it hard to contain my anger and disappointment about the way I believe my government is playing fast and loose with womens and girls’ safety.

Late on Saturday evening, scrolling through children’s pictures before I went to bed, I forgot the first rule of Twitter – never, ever expect a nuanced conversation – and reacted to what I felt was degrading language about women. I spoke up about the importance of sex and have been paying the price ever since. I was transphobic, I was a cunt, a bitch, a TERF, I deserved cancelling, punching and death. You are Voldemort said one person, clearly feeling this was the only language I’d understand.

It would be so much easier to tweet the approved hashtags – because of course trans rights are human rights and of course trans lives matter – scoop up the woke cookies and bask in a virtue-signalling afterglow. There’s joy, relief and safety in conformity. As Simone de Beauvoir also wrote, “… without a doubt it is more comfortable to endure blind bondage than to work for one’s liberation; the dead, too, are better suited to the earth than the living.”

Huge numbers of women are justifiably terrified by the trans activists; I know this because so many have got in touch with me to tell their stories. They’re afraid of doxxing, of losing their jobs or their livelihoods, and of violence.

But endlessly unpleasant as its constant targeting of me has been, I refuse to bow down to a movement that I believe is doing demonstrable harm in seeking to erode ‘woman’ as a political and biological class and offering cover to predators like few before it. I stand alongside the brave women and men, gay, straight and trans, who’re standing up for freedom of speech and thought, and for the rights and safety of some of the most vulnerable in our society: young gay kids, fragile teenagers, and women who’re reliant on and wish to retain their single sex spaces. Polls show those women are in the vast majority, and exclude only those privileged or lucky enough never to have come up against male violence or sexual assault, and who’ve never troubled to educate themselves on how prevalent it is.

The one thing that gives me hope is that the women who can protest and organise, are doing so, and they have some truly decent men and trans people alongside them. Political parties seeking to appease the loudest voices in this debate are ignoring women’s concerns at their peril. In the UK, women are reaching out to each other across party lines, concerned about the erosion of their hard-won rights and widespread intimidation. None of the gender critical women I’ve talked to hates trans people; on the contrary. Many of them became interested in this issue in the first place out of concern for trans youth, and they’re hugely sympathetic towards trans adults who simply want to live their lives, but who’re facing a backlash for a brand of activism they don’t endorse. The supreme irony is that the attempt to silence women with the word ‘TERF’ may have pushed more young women towards radical feminism than the movement’s seen in decades.

The last thing I want to say is this. I haven’t written this essay in the hope that anybody will get out a violin for me, not even a teeny-weeny one. I’m extraordinarily fortunate; I’m a survivor, certainly not a victim. I’ve only mentioned my past because, like every other human being on this planet, I have a complex backstory, which shapes my fears, my interests and my opinions. I never forget that inner complexity when I’m creating a fictional character and I certainly never forget it when it comes to trans people.

All I’m asking – all I want – is for similar empathy, similar understanding, to be extended to the many millions of women whose sole crime is wanting their concerns to be heard without receiving threats and abuse.